Of the sixty-eight thousand games on Steam about four thousand of them are Early Access, and of those about six hundred have made it to a full release. With a success rate of only fifteen percent it doesn’t seem too bright a concept, although, we don’t know the success rate of those game which didn’t try for a Traditional Release.

While there’s a scarce few I’ve seen that actually made it I’ve also seen some that have turned out impressive like Hollow Knight or Warframe, and I’d like to have been able to know before hand if it had any chance of success. So…

Is there a way to determine if an Early Access game is actually going to hit 1.0 or not?

It’s important to note that just because a game releases doesn’t mean that it’s a particularly good one; take Duke Nukem Forever for example. However, while quality is important to me we’re not going to focus on that too much here, all we care about is what features increase or decrease the probability of a developer keeping their word.

So, is there anything concrete that determines a game’s eventual release into 1.0? Let’s find out.

Overview

I started with a dataset of steam games from Craig Kelly at data.world and added onto it with some information from SteamSpy. SteamSpy definitely had a lot more recent data but unfortunately it’s a pain to get any of it. Regardless I used three models on my data and we’ll start with a baseline.

| Metrics | Baseline |

|---|---|

| Accuracy: | 0.3107932379713914 |

| Precision: | 0.3107932379713914 |

| Recall: | 1.0 |

Baselines are what the minimum effort would get us. If we can’t beat that with our model, we’re doing something wrong. In this case it’d get us about 30% accuracy when looking for games that have left Early Access in a random chunk of our data, so if you’re wondering where the 15% came from before, that was over the total games and total Early Access games on steam. My dataset doesn’t have all sixty-thousand games and this random selection happens to get more of the full releases.

| Validation Metrics | Random Forest Classifier | XGBoost Classifier | Logistic Regression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy: | 96% | 95% | 89% |

| Precision: | 97% | 92% | 88% |

| Recall: | 90% | 94% | 76% |

After running these three models we got these scores. For claficication, accuracy measures how much of the data was correctly identified in our validation set. With each at least near 90% we have a pretty decent level of confidence. But precision tells us how many were correctly identified versus not. For example with the Random Forest Classifier we correctly identified 97% Ex Early Access games while falsly marking another 3% as having released. Finally recall tells us how much of the total in the category we care about were selected. For example, in the Logistic Regression model we got 76% of the Ex Early Access games, but we missed another 24% of them.

Plots

Force Plots

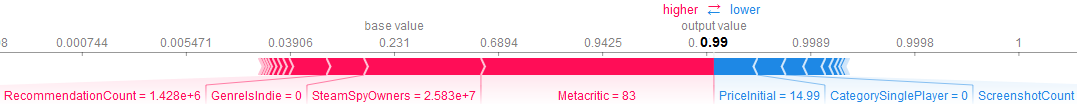

To start with I made a force plot with XGBoost to see more clearly which of the features made the most difference. For this we can see metacritic makes a big difference in the outcome, followed closely by the number of actual owners. We also see here that if the genre is indie it does have a negative impact, but this will be a little more apparent in the next plot.

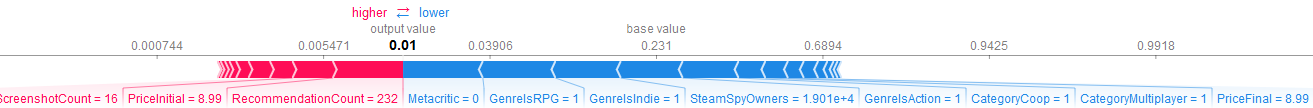

A low metacritic score again seems to indicate a game isn’t too good, but in this case if a game is indie or an rpg it seems to do even worse, on par with the low metacritic score.

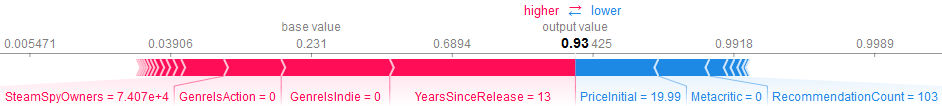

Here we also see that the number of years since it’s release into Early Access indicates that it’s probably made it to a full release, but the initial price is steep in comparison to other Early Access games.

PDP Plots

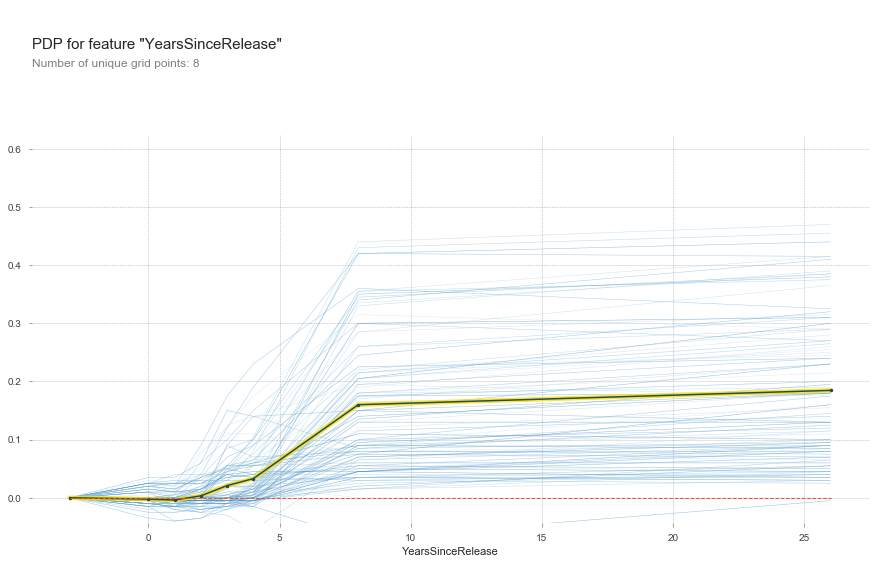

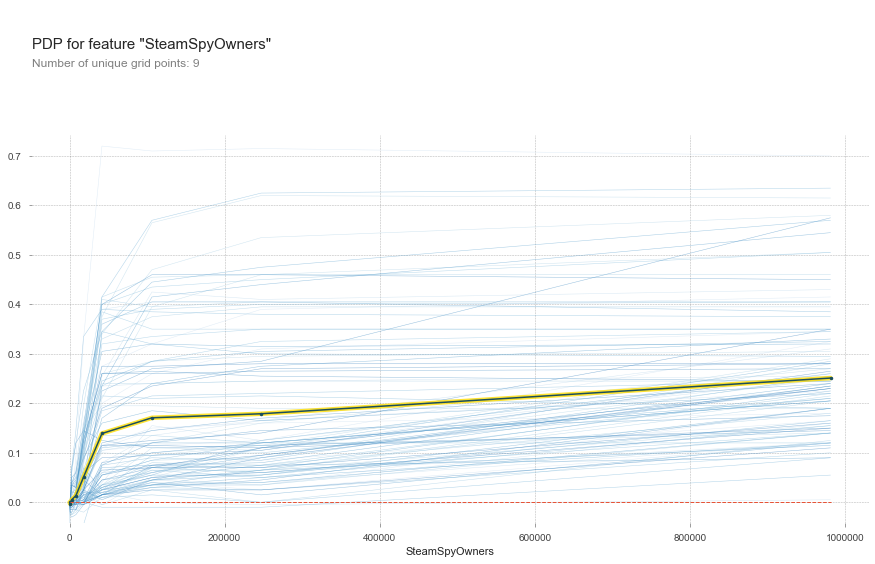

Since the release date wasn’t being used well by the model I decided to replace it with the games release dates and subtracted them by the current year. That tells us how long it’s been since it was released to Early Access, and as you can see as a game spends more time in development, generally it becomes more likely to release, though it’s not guarenteed.

This next plot is cut down substantially for readability, but suffice to say that as the number of adopters increases, so too does the chance of a game releaseing. However this doesn’t tell the whole story either; people don’t just adopt a game and ensure it releases, it may also be that people only flock to a game when it’s actually good, so let’s take a look at that too.

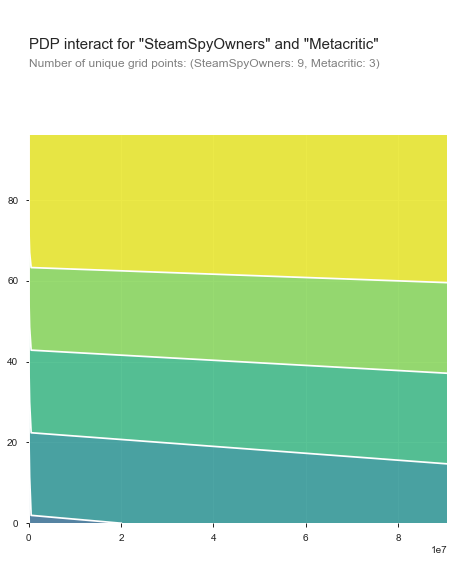

Now we can see that as we have more and more people, generally, the metacritic score will be higher. However we also see that it’s marginal at best; The difference between one and several thousand is maybe a point or two on metacritic. So while score matters, and the number of people matter, one does not cause the other.

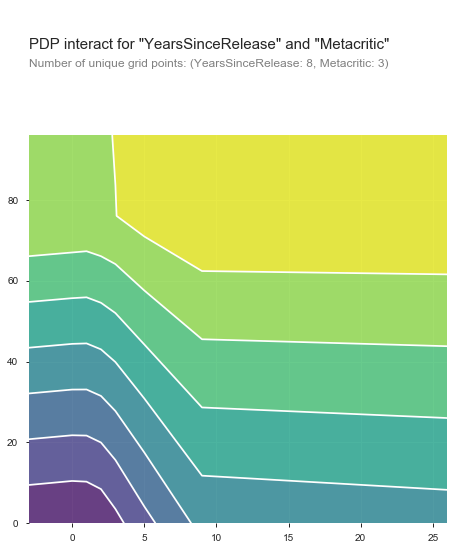

Probably the most interesting one here for the interact plots. We have Metacritic on the y axis and the years since a game’s release on the x axis. So what we’re seeing is that if a game is scoring highly, it’s very likely to release. If a game is taking awhile, it can become more likely to release, but not to the same level. When both are combined however, it’s significantly more likely.

At around the nine year mark though we start hitting the outliers that overwhelm this graph and pull it out to the right, there’s maybe about 11 of them in total.

Unfortunately…

It didn’t work out.

The main problem I came to realize in my project was that I was using information from these games that I wouldn’t have at the start of any game’s Early Access. I wanted to know the probability that a game would actually survive to 1.0, but if I didn’t have this information prior such as the metacritic score, I couldn’t actually take any action with these models. Which makes them equivalent to Sterling engines; Very neat, but completely useless for any serious application.

Conclusion

The only way you’re going to get something actionable from your data is if you actually work through the problem in your head, try to figure out what would tell you without machine learning in the first place, then try to test and be sure you’re on the right track before you go out crafting a nice, well-lit, finely dug hole in the ground.